Author: Allison Myatt, Senior Environmental Officer, Capital Planning

I arrived in Ottawa many years ago, having only once been here as a child to skate on the Rideau Canal. As a newcomer to the city and an avid runner, my priority was, of course, to find running trails that would allow me to explore different parts of the city. It was on one of those runs that I stumbled upon Victoria Island, a hidden gem within the downtown core. With its wild shorelines, historic buildings, Indigenous roots and panoramic views, I found myself stopping to take it all in.

As I wandered around, I started to notice that decades of past industrial use had left parts of the island in rough shape. But, from what I witnessed, this place had enormous potential.

So, when the environmental file for Victoria Island landed on my desk, I was ready to take on the challenge of helping to restore the island’s natural beauty, where visitors could safely visit the site and reflect on the incredible physical and cultural landscape of the area. How? By removing the most detrimental relics of its industrial past: contaminated soil, debris and, yes, potentially harmful gas cylinders.

So where to begin?

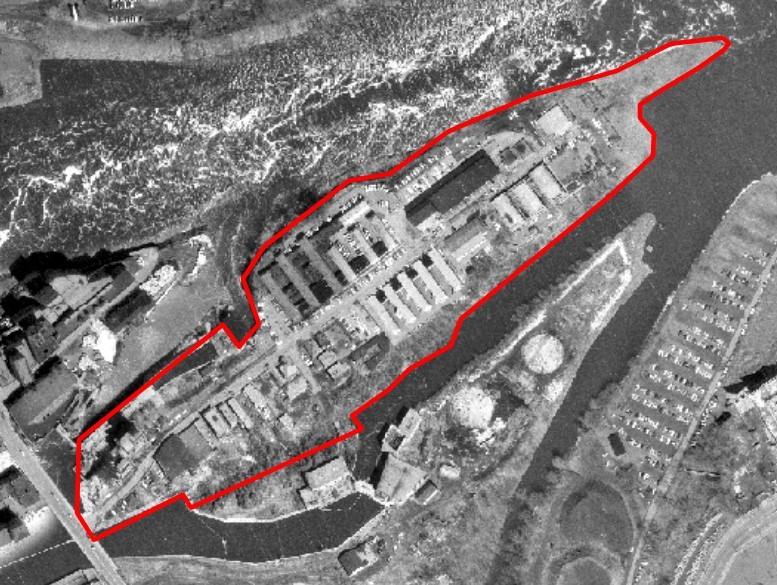

It all started in 2018, when the environmental condition of the island was re-evaluated. Victoria Island was a known contaminated site and, although levels of contamination were previously determined to be acceptable for site use, updated testing revealed that certain areas had greater levels of contaminants than originally documented.

With this new information, the conclusions of the original study were no longer valid, and the island required immediate intervention. In the short term, parts of the island were capped, and fences were put up to keep people out of certain areas. And, by the end of the year, the island was fully closed to the public. Let the cleanup begin!

Environmental remediation is not a simple task. And, with this project, every complexity you can think of was a reality on the island: steep slopes, a web of utilities, including high-voltage lines, asbestos, buried gas cylinders, archaeological and heritage resources, and, of course, legal agreements.

Let it slide!

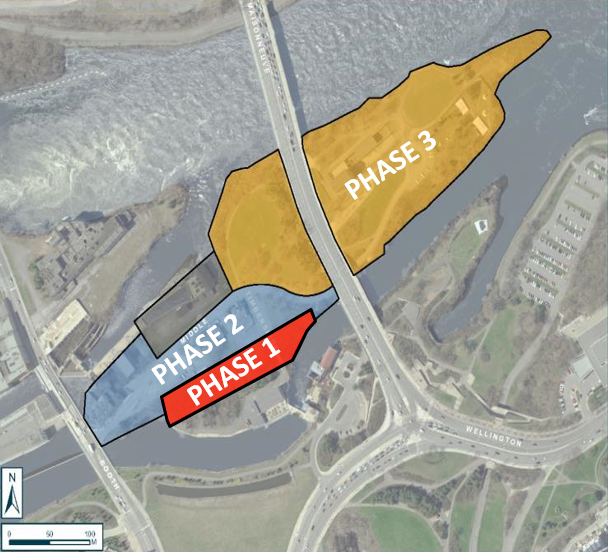

The first phase of work focused on the ravine on the south side of the island. The ravine was quite steep and narrow. However, it didn’t always look like this.

In the 1830s, the ravine was transformed into a timber slide, where the lumber industry could bypass the Chaudières Falls on the Ottawa River, and send their timber downstream. But, between 1906 and 1980, many different industries came and went on the island and, as the use of the timber slide dwindled, the industrial facilities gradually filled in the ravine with their waste and debris, contaminating the soil.

So, what was our plan? To remove all soil and debris to reveal the original bedrock surface of the timber slide. All said and done, over 13,000 metric tonnes of contaminated soil and debris were removed. Given the levels of contamination, the soil could not be beneficially reused off-site; all soil had to be transported to a landfill as contaminated waste.

The ravine looks dramatically different today, and more closely resembles the original timber slide of the 1800s. Although the original wooden cribbing of the timber slide is gone, a 1970s-era log flume remains in the ravine, and stands as a reminder of the island’s important contribution to the lumber industry.

An unexpected surprise

Perhaps I’ve made the remediation seem all too easy. Well, not so fast.

In preparation for the work, we found that the island was harbouring an unexpected surprise: pressurized compressed gas cylinders. It turns out that, from the early 1900s until 1966, there was an acetylene gas manufacturer and distributor on-site. At some point during the manufacturer’s tenure, close to 1,000 cylinders were buried, either under the concrete floor of one of the buildings or outside, underground. While most of the cylinders were inert (or had no pressure), a good number of them still contained gas. Acetylene gas is highly flammable and chemically unstable, which means that a small leak could lead to possible ignition and explosion. The cylinders were in poor condition and deteriorating, so this was a real risk.

This was such an exceptional case that we had to call in experts to help. A truly professional team, experienced in chemical, biological, radiological, nuclear and explosive threats, was recruited to the project. Decked out in specialized carbon-lined suits and full-face respirators, they were called to the site to manage this dangerous situation. And that they did, safely.

From trash to treasure

What else did we find? Well, at the outset of the project, we knew that we would encounter archaeological resources. The number and significance weren’t fully appreciated yet, but we were prepared.

Under the expert eye of the NCC’s archaeologist, Ian Badgley, the contractors were given training about the archaeological resources they might find on the site, and they played an active role in the recovery of these resources. Through careful excavation, complete glass bottles, jugs, saw blades, horseshoes and even a bicycle seat and furnace door were found.

One of the best finds? A very rare bottle of Florida Water, dating back to the 19th century. It’s basically scented water — just like eau de cologne. It was made in Toronto by a company that manufactured it for only a short period of time.

So, what’s next?

Cleaning up the island is expected to continue until 2025. To make it happen, we are relying on a team of experts: civil, structural, geological and environmental engineers; biologists; archaeologists and heritage experts; hazmat and industrial hygiene experts; legal teams; land managers; and landscape architects. We are also making efforts to include the Algonquin Nation in this project. Everyone has an important role to play.

For the next phase of the project, we are heading to the section north of the timber slide (Phase 2). Although presenting different challenges, it is expected to be equally as complex. Once complete, we will move to the east side of the island (Phase 3) and finish our work there before opening the site back up to the public.

So, you may be wondering what the future holds for the island? Well, as part of the remedial work, we will be landscaping in such a way as to facilitate implementation of the future vision for the island. Some areas of the site will look the same, some will look quite different. This is all part of a bigger plan. The NCC has committed to develop a master plan for the island, in partnership with the Algonquin Anishinabe Nation. However, until the vision is developed and implemented, the site will be open for the public to enjoy.

The past two years have been eventful, to say the least. It is a privilege to be part of such an interesting team on such a high-profile project, and I’m excited about the next phase.

After the work is complete and the island is reopened, I hope that our attempts at balancing the requirements of modern-day remediation with the desire to preserve the island’s past will be apparent, and that there will be general appreciation for the complexity of the work.

For me, personally, I know that my running route will take me to the shores of Victoria Island, where I will be able to sit and reflect on what will undoubtedly be a proud example of the incredible physical and cultural landscape within Ottawa’s downtown core.