Cassandra Demers

Content Strategist

Gatineau Park is the national capital’s conservation park, a haven for both wildlife and outdoor enthusiasts. The park receives about 2.6 million visits every year, which puts a lot of pressure on its wildlife and ecosystems.

The NCC has introduced a limited schedule for personal motor vehicle access for three parkways in Gatineau Park: Champlain, Fortune and Gatineau parkways. This aims to protect wildlife and allow people to fully enjoy what the park has to offer in a car-free environment. Although this initiative is widely supported, one question remains: how effective is it in protecting wildlife?

That’s what Carleton University master’s student Lilli Gaston is determined to find out. I met with her to discuss the research project she is conducting.

Gatineau Park, the perfect setting for this study

Q: Lilli, can you give us some context for your study and explain what prompted it?

A: Absolutely! Studies have shown that roads can reduce habitat connectivity, increase animal mortality and even impair habitat quality with traffic noise, pollution and other factors. They are especially dangerous at the urban-wildland interface, where roads cut through areas with high densities of animals. [source]

Solutions, such as wildlife crossing structures, fences and speed limits, exist, but they are costly and not always effective. Periodic road closures, like those in Gatineau Park, offer a low-cost solution that also considers the need for human recreation and access to nature. Our goal with this study is to determine if this solution is effective in protecting wildlife.

My supervisor, Dr. Rachel Buxton, is committed to making a difference for biodiversity conservation and environmental justice. She founded Biodiversity Conservation Solutions, a research group focused on finding solutions that contribute to a shift towards a sustainable and equitable future, for the benefit of humans and wildlife.

The periodic road closures in Gatineau Park have created the perfect natural setting for an experiment like ours. Dr. Buxton proposed the project to the NCC, which decided to help fund it as part of its annual Scientific Research Support Program. The Friends of Gatineau Park also chose to support this project. Since conservation solutions are near and dear to my heart too, I knew I wanted to be a part of it. And now we’re here.

Gathering data

Q: How will you measure whether it’s effective or not?

A: We will be looking at bird and mammal diversity and direct wildlife mortality. For this study, we have distinguished three types of roads:

- periodically closed (e.g. Gatineau Parkway, Champlain Parkway and Fortune Lake Parkway);

- permanently closed (e.g. Gatineau Parkway between parking lots P8 and P9, also known as the North Loop); and

- permanently open (e.g. municipal roads).

From May to August 2023, we collected data on each of these types of roads and in forested areas next to them.

To assess bird and mammal diversity, we used passive, non-invasive monitoring techniques:

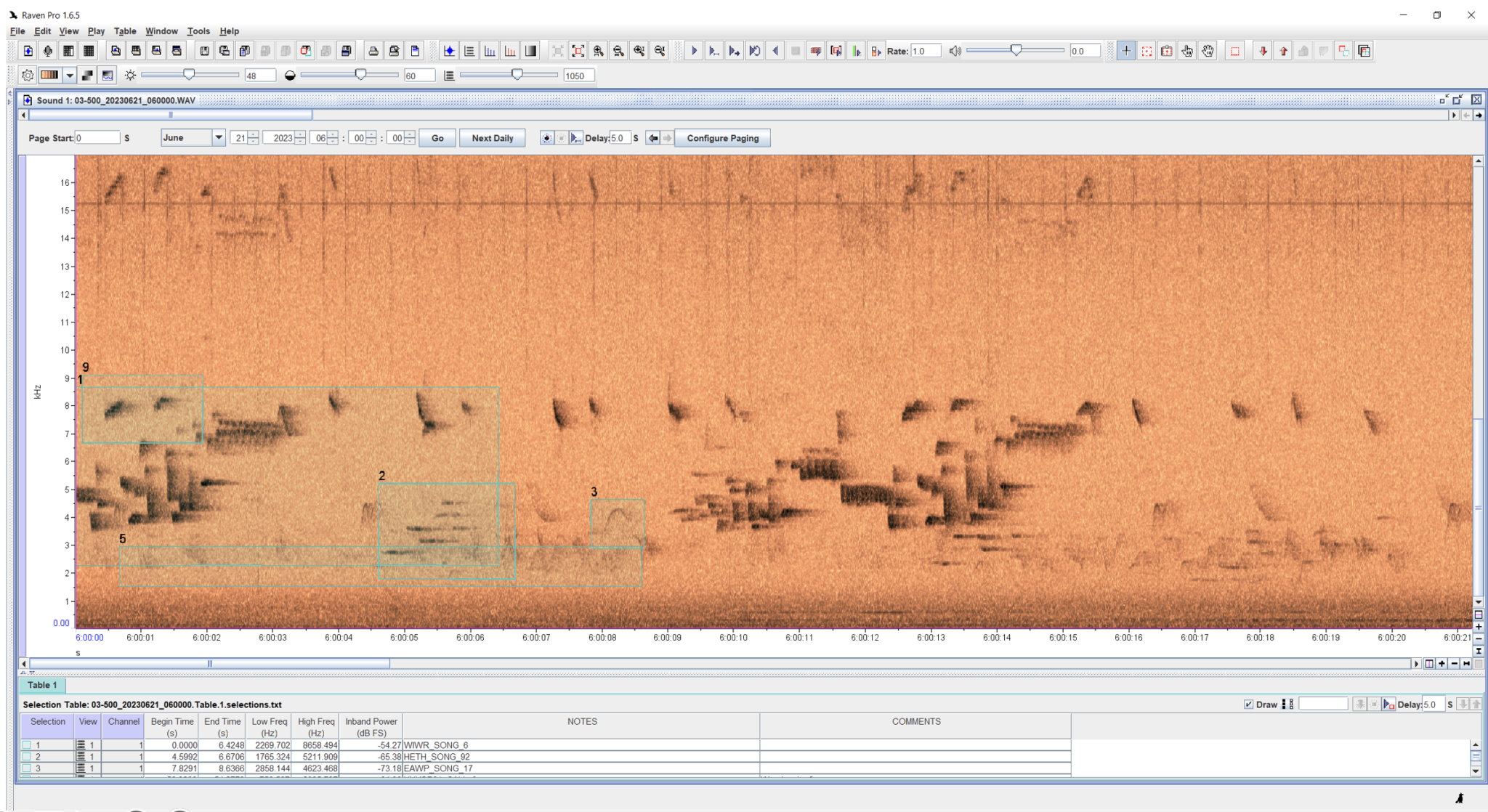

- acoustic recording devices for birds; and

- motion-activated wildlife cameras for mammals.

I had worked with both techniques before coming to Carleton, and it just made sense to reuse them here. We installed the devices at either 100 m or 500 m from any road, to explore differences relative to distance to roads.

To measure direct wildlife mortality from vehicle collisions, we surveyed roads using an electric-assist bicycle. We went out twice a week over three months in 2023 to count and identify road deaths.

Q: What exactly are you looking for?

A: For birds, we measure species richness and abundance, overall community composition and the presence of indicator species commonly found in Gatineau Park. Specifically, we are interested in birds that breed in the forest and have varying sensitivities to human disturbance, like the Ovenbird, the Eastern Wood-Pewee and the Wood Thrush.

The Eastern Wood-Pewee (species of special concern) and the Wood Thrush (threatened species) are listed under the federal Species at Risk Act. The Ovenbird is classified as least concern by the International Union for Conservation of Nature.

For mammals, we measure species richness and the presence of indicator species commonly found in Gatineau Park. Specifically, we are looking for species that are sensitive to roads and traffic, such as the black bear and the fisher, as well as those more tolerant of roads and traffic, such as the white-tailed deer, eastern coyote and raccoon.

For direct wildlife mortality, we measure roadkill abundance and mortality rates across species and taxonomic groups.

Preliminary results

Q: Do you have any preliminary results to share?

A: Here are the preliminary results from our first field season. Keep in mind that these have yet to be analyzed.

Based on the acoustic recordings listened to so far, we have identified 43 different bird species. We detected Ovenbirds at 90% of recorders, the Eastern Wood-Pewee at 65%, and the Wood Thrush at 7%. However, this is just from a small sample of our total recordings. We are still in the process of transcribing the data with the help of volunteers from the Friends of Gatineau Park, so more results are yet to come!

There is just so much data to go through, but we are very encouraged by the use of BirdNET. This AI tool can help us identify species automatically, with a confidence threshold up to 100% certainty. It will really help us get through the huge amount of acoustic data we have collected.

The wildlife cameras have captured a total of 21 unique species, 14 mammal species and seven bird species, across all road types. The most commonly detected species is the raccoon, followed by white-tailed deer, black bears, wild turkeys, grey squirrels, eastern coyotes, red foxes and fishers. We even saw a moose, which is rare in Gatineau Park!

Across 45 km of surveyed roads, over three months, we found 328 road-killed animals, representing 24 different species. In Gatineau Park, amphibians are by far the most frequent victims of road accidents, followed by reptiles, mammals and birds. Amphibians and reptiles are more vulnerable on roads because they:

- lack avoidance behaviour;

- move slowly when crossing; and

- have seasonal migrations (e.g. amphibians crossing roads in great numbers to reach breeding ponds, turtles reaching nesting sites, snakes thermoregulating on the road surface).

Next steps

Q: What are the next steps?

A: We completed the first year of data collection in the summer of 2023. We will be setting up again in May 2024 for our second and last year of data collection, in the same locations, with the same setup. We should have a complete set of data to look at by fall 2024, and then we will dive into analysis.

By the end of the data collection phase, we will have collected so much data that it will be challenging to cram it all into my master’s thesis. I’m so grateful that we’ll have a new field tech, Laura, in 2024, an undergrad student doing her honours thesis in Buxton’s lab. Laura will be looking at roadkill data specifically, so we will be able to thoroughly explore all our datasets.

My hope is that this study can inform the NCC’s efforts in maintaining healthy and biodiverse bird and mammal populations and showcase how humans and wildlife can share the landscape. I feel very lucky to be a part of this important project, and I cannot wait for the upcoming field season!

The diversity of ecosystems in Gatineau Park and NCC Urban Lands makes them ideal places for research, and even more so because they are near the Capital’s scientific institutions.

Each year, the NCC grants approximately 40 scientific research permits in Gatineau Park and on Quebec urban lands. The results of these studies help our biologists and managers plan the short- and long-term protection of species, habitats and ecosystems.