Jane Wakiwaka

Sustainability Manager at The Crown Estate

Looking upwards is becoming a critical element of our design vocabulary. On February 15, 2018, the NCC’s Urbanism Lab program explored the varied elements of planning the sky.

Three industry experts gave their perspectives on how planning the sky is shaping our cities:

- Jane Wakiwaka, Sustainability Manager, The Crown Estate, and Wild West End in London, United Kingdom (U.K.)

- Dr. Christine Sheppard, Director, Glass Collisions Program, American Bird Conservancy

- Rémi Boucher, Scientific Coordinator, Mont-Mégantic International Dark Sky Reserve

Green infrastructure

As a sustainability manager for The Crown Estate, Jane Wakiwaka is responsible for developing sustainability strategies for new developments and existing buildings across the company’s central London portfolio. The organization’s integrated approach to sustainability led to the development of a London ecological master plan. It aims to create over a hectare of new green space across its London assets by 2030.

Wild West End

In recent years, common species such as birds, bees and bats have been in decline throughout the U.K. In response to this, efforts to protect and support London’s wildlife have become a priority. Originally, The Crown Estate sought to create a green corridor to link Regent’s Park and St. James’s Park, by connecting green spaces across its commercial buildings in central London, but identified a greater opportunity to establish a network of green spaces through partnerships.

In 2015, The Crown Estate teamed up with other landowners within London’s West End (i.e. Grosvenor Britain & Ireland, Shaftesbury, The Portman Estate and the Howard de Walden Estate), in addition to Arup (as technical partners), the London Wildlife Trust and Greater London Authority (as strategic partners) to launch Wild West End. The Wild West End initiative introduces green pockets among the hustle and bustle of the city.

The partnership was inspired by a mutual desire to strategically improve biodiversity, as well as raise awareness of the importance of green infrastructure. “Issues such as the lack of biodiversity in London’s West End have an impact on all the partners involved. By working in partnership, we are able to collectively deliver more biodiversity to address these issues, and create a destination where people want to be. By focusing on biodiversity and its associated benefits — such as health and well-being — for people who visit, live or work in the area, Wild West End is a great example of how this can be achieved,” says Wakiwaka.

Gardens on rooftops

The limited opportunity to create green spaces at ground level in central London is pushing Jane and her team to get creative. They are achieving their goal through a combination of green infrastructure at street level and on rooftops.

The biodiverse roof at 7 Air Street provides 150 square metres of new wildlife habitat. It was designed to encourage as many species as possible throughout the year.

Log piles were added to create habitats for species that are essential for pollination, such as spiders, bees and wasps. Nesting boxes were also installed to re-attract the rare black redstart, and solar panels create an array of microclimates to encourage further biodiversity.

The green terraces at 10 New Burlington Street help enhance biodiversity and provide accessible green spaces so that people can feel closer to nature throughout the day. Trees and a green wall create a natural space where occupants can work and relax. The flowering plants attract butterflies and bees during the day, and moths and bats at night.

The rooftop initiatives of Wild West End are also brought to the streets through The Crown Estate’s Summer Streets series, which sees Regent Street closed to traffic every Sunday in July. The road is filled with pop-ups, live music, exhibits, food and drink. In 2017, more than 1.8 million people visited Summer Streets events. The Crown Estate also brings bees to meet the public with the resident beekeepers on hand to provide information about wildlife and biodiversity across Regent Street. Visitors were also given the opportunity to make their own bug hotels, and given plants and seeds to take home.

The aim of Wild West End:

- Improve the well-being of residents, workers and tourists by increasing connections to green space and nature.

- Contribute to improvements in local air quality.

- Enhance biodiversity and ecological connectivity by creating new habitats.

In the end, The Crown Estate and its partners hope that the project will inspire others to take on similar initiatives all over the world.

A bird’s-eye view

Birds play an important role in the world we live in. They consume vast quantities of insects and control rodent populations, reducing damage to crops and forests. They also play a vital role in regenerating habitats by pollinating plants and dispersing seeds.

Christine Sheppard of the American Bird Conservancy has worked with birds for many years. Recently, she is seeing an increase in focus on how birds move from one place to another. “Birds spend a lot of their lives in the sky, which is why it’s so important to plan the sky the same way we plan our parks,” says Sheppard. She adds that planning our skies can help keep birds safe by reducing threats such as light pollution and hazards that can lead to bird collisions.

Light pollution

Urban lighting is luring birds into urban areas, a major factor in bird deaths. Many cities are adopting Lights Out programs to raise awareness of the problem light pollution poses for birds. However, these may not go far enough. According to Sheppard, reducing light from a few tall buildings isn’t enough to have a real impact, as even street lighting can attract birds into danger.

Capital Illumination Plan

The NCC prioritizes the protection of critical habitats by minimizing the impact of light pollution within ecologically sensitive zones.

Sheppard adds that the well-being of birds should be taken into consideration when cities design new structures. The 9/11 Memorial is an example of how the design of a structure can be harmful to birds if they are an afterthought in the planning process. It is known that a bright beam of light in a dark area can trap birds, causing them to circle in the light. When the 9/11 Memorial was proposed, local bird groups took part in negotiations, and now monitor the light when it is illuminated one day each year. If birds accumulate in the beam, volunteers make a call and the lights are briefly turned off. This type of action inspired Lights Out programs but, today, because light pollution is so pervasive, the “beacon effect” is less common.

Sheppard says the positive thing about this occurrence is that we now have data on the impacts of artificial light in areas where light pollution is ongoing.

Bird collisions

One of the biggest threats that birds face in urban areas is the potential for collisions. If a bird were to hit your office window, you might think it’s a rare occurrence. Sadly, this is not the case. In North America, up to 1 billion birds die from hitting glass windows and walls every year.

The good news is that bird-friendly strategies are being applied to buildings — and with increasing popularity. These strategies fall into three categories:

- Using minimal glass

2. Placing glass behind some type of screening

3. Using glass with inherent properties that reduce collisions

Sheppard says the New York Times building is a great example of what it means to be bird-friendly. The building was originally designed with the intent of conserving energy. However, the sustainable design serves another function: it deters birds.

- The front of the building is covered in horizontal ceramic rods, spaced to enable people to see out the window, while reducing the amount of exposed glass.

- Around the corner, the building has a ceramic material screened on the glass to control the amount of heat and light coming through the window in the summer months. Because the patterns are big enough for birds to see, they fly around the building.

You can also play a role in keeping our birds safe. Here are a few things you can do to make your home more bird-friendly.

Seeing stars

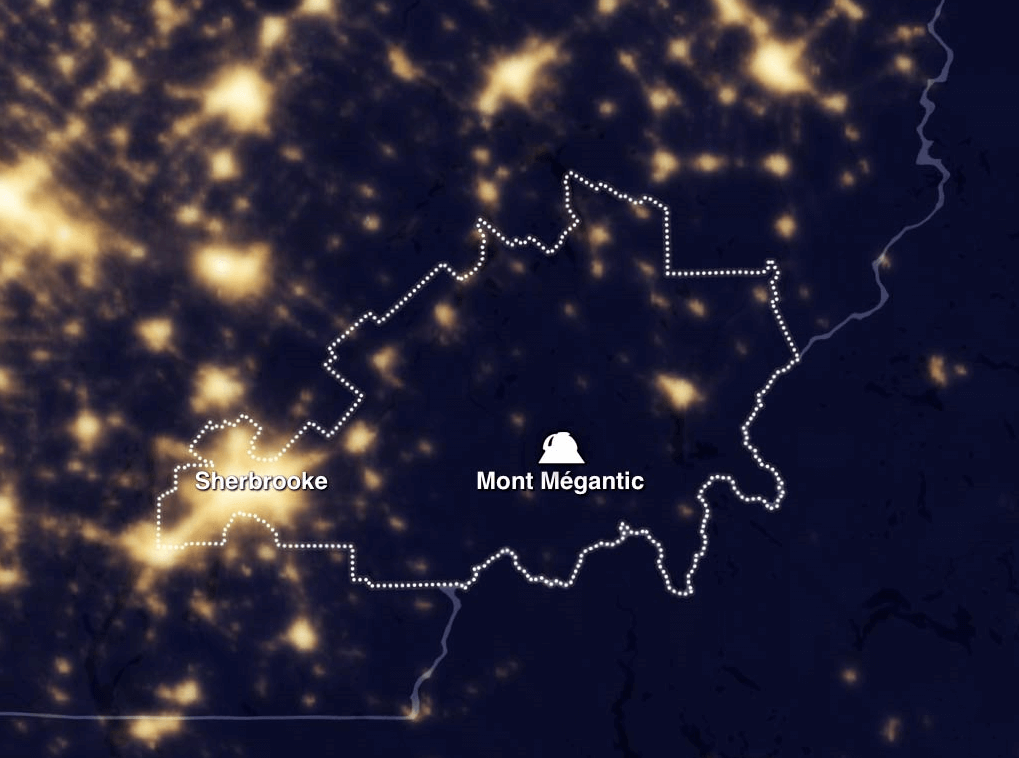

Rémi Boucher explains that planning the sky gives people access to the starry night sky, without compromising their safety and security. The Mont-Mégantic International Dark Sky Reserve is a leading example of this balance. Founded in September 2007, the reserve stretches over 5,275 km2 of land, including a national park and Mont-Mégantic observatory, the city of Sherbrooke and other municipalities.

By reducing light pollution, the reserve gives people from the surrounding cities the dark sky experience that they are missing. For example, Montréal’s population can see only 100 stars, at most, in the sky compared with the more than 3,000 stars visible from the Mont-Mégantic International Dark Sky Reserve.

Impacts of light pollution

According to Boucher, light pollution is a set of disturbances caused by nighttime artificial lighting that is poorly designed or poorly used.

One of the most obvious impacts of light pollution is decreased visibility of the starry night sky. Sky glow happens when too much artificial light is emitted into the sky. This is why you have to drive a few hundred kilometres outside of the urban core to see the Milky Way.

Light pollution also has an impact on our environment, as many species depend on natural light cycles to hunt, eat and sleep.

- Bats are leaving nesting sites as they become too heavily lit.

- Hatching turtles use the light from the moon and stars reflected on the water as a guide toward the sea. However, artificial lights on the shores confuse young turtles, making them vulnerable to predators.

- Insects and moths are attracted to light, and will fly around light bulbs for entire nights, dying of exhaustion or heat, which in turn impacts the food chain.

- Excessive light in large urban areas confuses migratory birds’ sense of orientation, and increases the number of collisions with buildings.

Human health is also impacted by light pollution, because melatonin, an essential hormone, can be secreted only when we sleep in darkness. When there is too much light, especially blue light, while we sleep, our biological clock gets thrown off; over time, this can cause health problems. An American Medical Association study found that even small amounts of LED lighting in our environment can suppress the production of melatonin.

Many cities that recently switched over to LED street lights have received so many complaints that they are replacing the newly installed street lights.

Solutions

“There are four lighting principles that must be respected in order to reduce the negative impacts of light pollution,” said Boucher. These principles are as follows:

- Adjust the orientation toward the area or building.

- Choose lights of a warm colour over blue lights.

- Reduce excessive light intensity.

- Limit the time and length of use to what is necessary.

Boucher says the High Line in New York City is an example of a project that has successfully adopted most of these lighting principles. The High Line’s lighting system projects just enough light to keep pedestrians safe, and at the same time ensure that the evening scenery is visible from the park.

They chose to use warmer tones in their lighting, and installed the fixtures such that they are hidden, which creates the effect of a pleasant, subtle glow. The lighting is oriented such that it is no higher than waist level, thus reducing glare.